Perhaps my expectations were a bit lofty—taking English IV students with the type of full-blown senioritis May tends to inflict and thrusting them into writing groups. (See my previous blog entry—It all started with a budgeting activity in English class—for more about what prompted this.) As with anything in life, my students got out of this collaboration what they put into it.

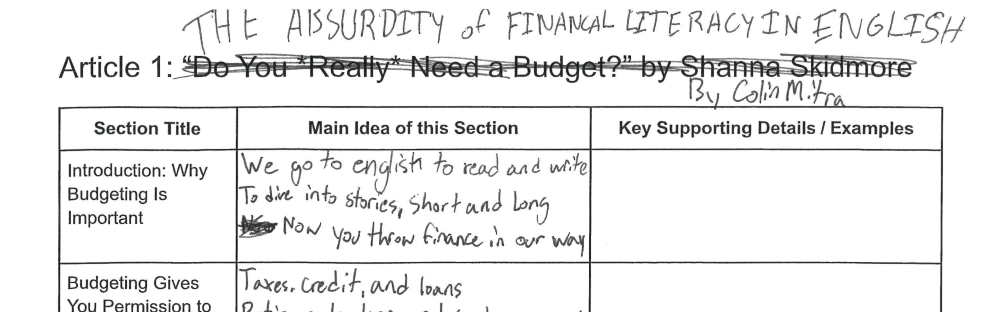

On a Pre-Writing Groups Survey, students assessed how comfortable they were giving constructive feedback to others using a Likert scale on which 1 indicated cool confidence and 5 deemed the activity tantamount to torture. Of the 29 students who completed the Pre-Writing Groups Survey, 37.9% reported feeling moderately comfortable providing peer feedback, and 48.2% indicated a higher level of comfort. (See Figure 1.) And, of those surveyed, only 37.9% recalled having participated in peer writing groups previously.

Before we began, we discussed (in our groups, then as a whole class) our initial concerns about sharing our writing. Students echoed sentiments of the vulnerability in sharing a piece of writing—the risk of being judged—and brainstormed ways to address this fear when their writing groups meet.

Then, we dove in. First, descriptive paragraphs. Then, poems. Finally, we worked on what we dubbed their “Senior Projects,” for which they had three options: a time capsule, a vision board, or a high school survival guide. Each Tuesday and Thursday, they brought a different piece for their projects—reflections, explanations, letters, top ten lists, text for infographics, and articles—to their writing groups.

A few embraced it wholeheartedly. Yadissa, a natural born leader, took her group’s participation to the highest level. Some of these conversations were the most heartwarming, hearing her work one on one with Angel, an English language learner, when the third member of their group was (frequently) absent. Yadissa guided Angel, helping him better understand the vision board option and how best to approach it. She encouraged him to elaborate and complimented him on his willingness to make himself vulnerable in his writing. In turn, Angel posed a couple of thought-provoking questions and made some practical suggestions for Yadissa’s high school survival guide.

Some kicked around a few compliments as well as constructive criticism. Madi’s group was the most boisterous, providing a balance of helpful feedback, such as sincere appreciation for the details and depth of Aiden’s writing, with shock over the length and impressive (intimidating?) quality of Madi’s writing. They had fun with it.

Some did the bare minimum, but even those kiddos were sharing their experiences, their dreams, their wisdom—and their writing. While their feedback may have been superficial at best, several groups had rich conversations at times, even though the response forms they filled out may not have reflected it.

On a Post-Writing Groups Survey the last week of school, every response indicated a positive feeling toward writing groups, declaring it “fun” or “good,” noting how nice it was to receive feedback from peers. All also indicated they would recommend participating in writing groups to other students. Aiden commented, “Yes, it is very eye opening. It is always good to look at something from a different perspective.”

Keyonna indicated the most beneficial part of participating in writing groups was “having multiple people giving advice or compliments.” Yadissa noted, “It made me open and considerate to others more than before. We would push each other into making the best out of our writing pieces. I was very fond of the self-motivation aspect of working in a writing group.”

Yadissa also offered interesting insight into what she considered the most challenging part of participating in writing groups: “Every now and then, some of us would get indecisive before wanting to submit and talk about our work. So sometimes we would try to revise and change our work completely before we reached that step. So as much as I’d like to say we leaned on each other for feedback, we sometimes pushed for it before it was time to.” Others cited the difficulty in providing quality feedback, struggling to come up with suggestions for improvement.

Of the 14 students who completed the Post-Writing Groups Survey, 21.4% indicated an average comfort level when it comes to providing peer feedback, and 64.3% reported a higher than average comfort level. (See Figure 2.) Thus, in the mere weeks we experimented with writing groups, the average level of comfort with providing peer feedback increased approximately 16%.

We definitely could have benefitted from more time and more coaching. Nevertheless, these young adults entered the struggle of awkwardly navigating peer writing groups. However late in the year we began, and however half-heartedly some may have approached it, we were building a community of writers.